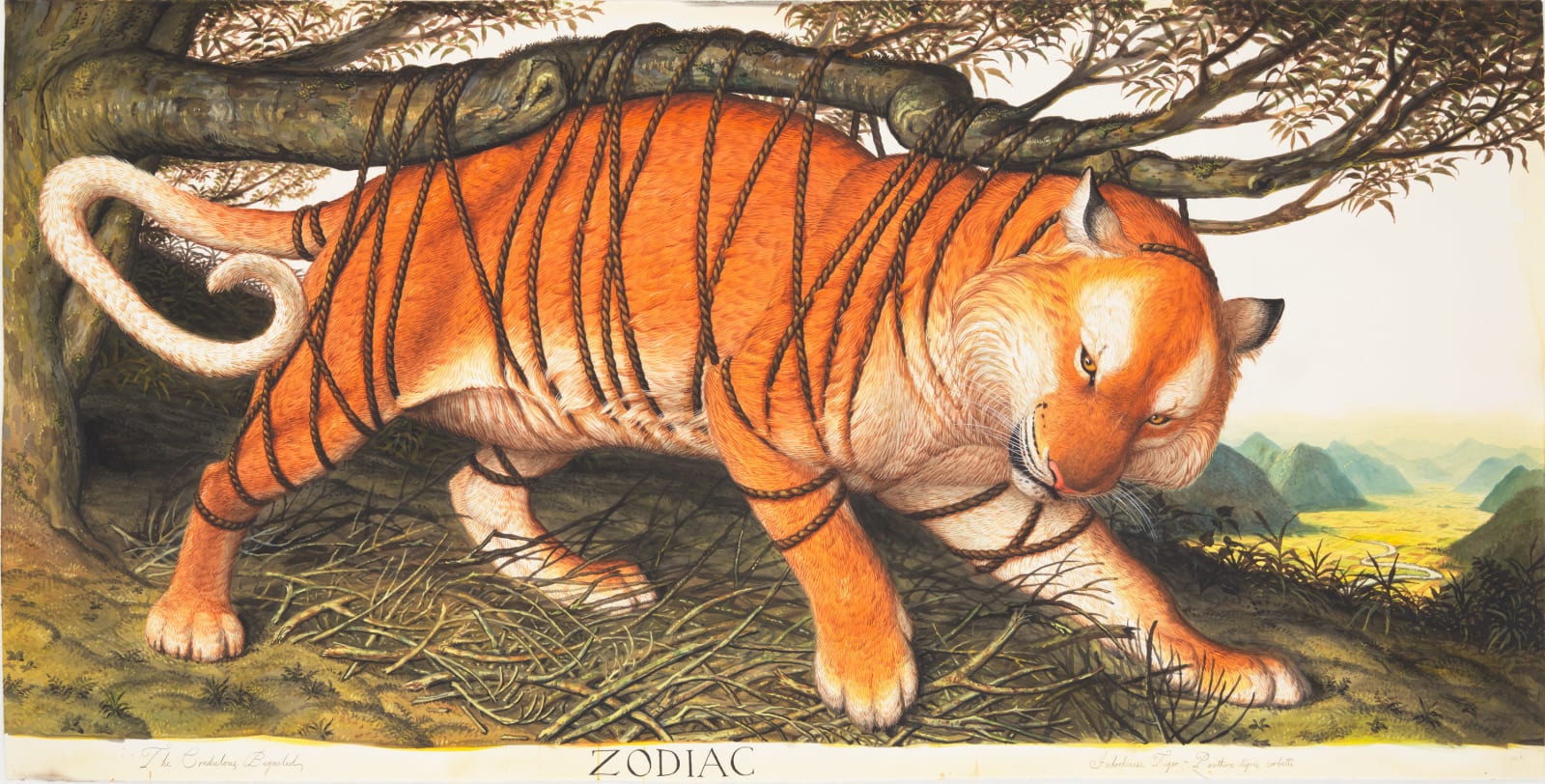

Walton Ford

Zodiac, 2014

watercolor, gouache, ink and pencil on paper

60 1/2 x 119 1/2 inches

153.7 x 303.5 cm

153.7 x 303.5 cm

Zodiac is a stunning example of Walton Ford’s monumental watercolor paintings, widely celebrated for expanding the narrative potential of natural history painting to subvert the genre’s conventions. A massive, bright...

Zodiac is a stunning example of Walton Ford’s monumental watercolor paintings, widely celebrated for expanding the narrative potential of natural history painting to subvert the genre’s conventions. A massive, bright orange tiger without stripes stands at the top of a hill, its tail curled and its head bent forward. A rope entangles the painting’s protagonist and binds him to a long, horizontal tree branch. Twitching its tail and ears in frustration, the tiger appears to realize he has just been tricked, characterizing Ford’s broader meditations on the intersections of human culture and the natural world. As the artist explains, “Zodiac is part of a series where I explore imagery from a Vietnamese folktale about how the tiger got its stripes. I was interested in the difference between someone reading a whimsical story like this, and what it would be like for the animal to actually experience this scenario in reality” (Walton Ford, 2022).

Executed in 2014, Zodiac is one of four paintings recounting a Vietnamese folktale from The Asian Animal Zodiac, a popular collection of stories authored by Ruth Q. Sun and first published in 1974. The present work represents the first scene in these paintings’ narrative sequence. The story begins when a tiger, who has a beautiful golden coat with no markings, sees a farmer beating his buffalo while plowing through a field. Angered by this mistreatment, the tiger scolds the buffalo for subjecting himself to such abuse by a human physically smaller than him. The buffalo replied that he was under the control of the farmer, who had something the much larger animals lacked: intelligence. Unfamiliar with yet intrigued by the concept of intelligence, the tiger asked the farmer where he kept this weapon. The farmer offered to fetch his intelligence from home, under the condition that he tie the tiger to a nearby tree so he would not eat the buffalo in the meantime. Believing the farmer’s promise to untie him upon his return, the tiger agreed, only to find he had been tricked when the farmer set him aflame. The tiger struggled to escape, eventually bursting out of his bonds but only after his fur underneath the rope had burned black, and the tiger thus learned the meaning of intelligence (Ruth Q. Sun, The Asian Animal Zodiac, 1974; excerpt published in Walton Ford: Pancha Tantra, 4th ed., Cologne, Taschen, 2020, p. 55).

The artist’s related paintings expand upon this narrative arc: Trí Thông Minh (2013) depicts the tiger leaping through the air after bursting through the rope, Cháy (2022) shows the tiger diving into a pool of water, and Hổ Vằn (2021) portrays the tiger sitting in water.

The image of the tiger is especially significant in Ford’s oeuvre. The first watercolor that he realized at this scale was an intricately detailed portrayal of a tiger, at a time when Ford had chiefly painted birds. The artist has recalled a trip to India in the 1990s where he marveled in life-size paintings by court painters who measured the bodies and modeled the unique stripes of the tigers their maharajas would shoot. The immediacy of those paintings called to the artist’s mind the naturalist painter John James Audubon (1785-1851), whose own life-size paintings of birds heavily informed Ford’s early painting practice. The thrilling discovery of a particular portrait of a tiger shot in the 18th century led the artist to produce his own, entitled Thành Hoàng (1997). That work was prominently featured in Ford’s mid-career traveling survey, organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 2006, which was titled Tigers of Wrath. That tiger’s stripes narrate Vietnamese martial history to condemn the legacy of colonialism that haunts that country, but a glass ball at its feet blurs the line between Vietnamese folklore and another fable about a tiger, local to ancient Iran and found in a medieval bestiary (Walton Ford, interview with Faye Hirsch, “King of Beasts,” Art in America, October 2008, p. 138.)

In comparison, Zodiac epitomizes Ford’s focused, mature style. It demonstrates the artist’s innovative method of storytelling drawn from his extensive research practice, narrating the consequential implications of the Anthropocene epoch on the life of this fabled animal. Ford’s painting practice has earned him international acclaim, and exhibitions of his watercolors have been staged at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, the Norton Museum of Art, Florida, and the San Antonio Museum of Art, Texas (2006-08); the Hamburger Bahnhof–Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Albertina, Vienna, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark (2010-11); and the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris (2015-16). Ford’s monumental watercolors can be found in such collections as Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Bentonville, AR; New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, CT; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS; and Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT.

Executed in 2014, Zodiac is one of four paintings recounting a Vietnamese folktale from The Asian Animal Zodiac, a popular collection of stories authored by Ruth Q. Sun and first published in 1974. The present work represents the first scene in these paintings’ narrative sequence. The story begins when a tiger, who has a beautiful golden coat with no markings, sees a farmer beating his buffalo while plowing through a field. Angered by this mistreatment, the tiger scolds the buffalo for subjecting himself to such abuse by a human physically smaller than him. The buffalo replied that he was under the control of the farmer, who had something the much larger animals lacked: intelligence. Unfamiliar with yet intrigued by the concept of intelligence, the tiger asked the farmer where he kept this weapon. The farmer offered to fetch his intelligence from home, under the condition that he tie the tiger to a nearby tree so he would not eat the buffalo in the meantime. Believing the farmer’s promise to untie him upon his return, the tiger agreed, only to find he had been tricked when the farmer set him aflame. The tiger struggled to escape, eventually bursting out of his bonds but only after his fur underneath the rope had burned black, and the tiger thus learned the meaning of intelligence (Ruth Q. Sun, The Asian Animal Zodiac, 1974; excerpt published in Walton Ford: Pancha Tantra, 4th ed., Cologne, Taschen, 2020, p. 55).

The artist’s related paintings expand upon this narrative arc: Trí Thông Minh (2013) depicts the tiger leaping through the air after bursting through the rope, Cháy (2022) shows the tiger diving into a pool of water, and Hổ Vằn (2021) portrays the tiger sitting in water.

The image of the tiger is especially significant in Ford’s oeuvre. The first watercolor that he realized at this scale was an intricately detailed portrayal of a tiger, at a time when Ford had chiefly painted birds. The artist has recalled a trip to India in the 1990s where he marveled in life-size paintings by court painters who measured the bodies and modeled the unique stripes of the tigers their maharajas would shoot. The immediacy of those paintings called to the artist’s mind the naturalist painter John James Audubon (1785-1851), whose own life-size paintings of birds heavily informed Ford’s early painting practice. The thrilling discovery of a particular portrait of a tiger shot in the 18th century led the artist to produce his own, entitled Thành Hoàng (1997). That work was prominently featured in Ford’s mid-career traveling survey, organized by the Brooklyn Museum in 2006, which was titled Tigers of Wrath. That tiger’s stripes narrate Vietnamese martial history to condemn the legacy of colonialism that haunts that country, but a glass ball at its feet blurs the line between Vietnamese folklore and another fable about a tiger, local to ancient Iran and found in a medieval bestiary (Walton Ford, interview with Faye Hirsch, “King of Beasts,” Art in America, October 2008, p. 138.)

In comparison, Zodiac epitomizes Ford’s focused, mature style. It demonstrates the artist’s innovative method of storytelling drawn from his extensive research practice, narrating the consequential implications of the Anthropocene epoch on the life of this fabled animal. Ford’s painting practice has earned him international acclaim, and exhibitions of his watercolors have been staged at the Brooklyn Museum, New York, the Norton Museum of Art, Florida, and the San Antonio Museum of Art, Texas (2006-08); the Hamburger Bahnhof–Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Albertina, Vienna, and the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebaek, Denmark (2010-11); and the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature, Paris (2015-16). Ford’s monumental watercolors can be found in such collections as Crystal Bridges Museum of Art, Bentonville, AR; New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, CT; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C.; Spencer Museum of Art, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS; and Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT.